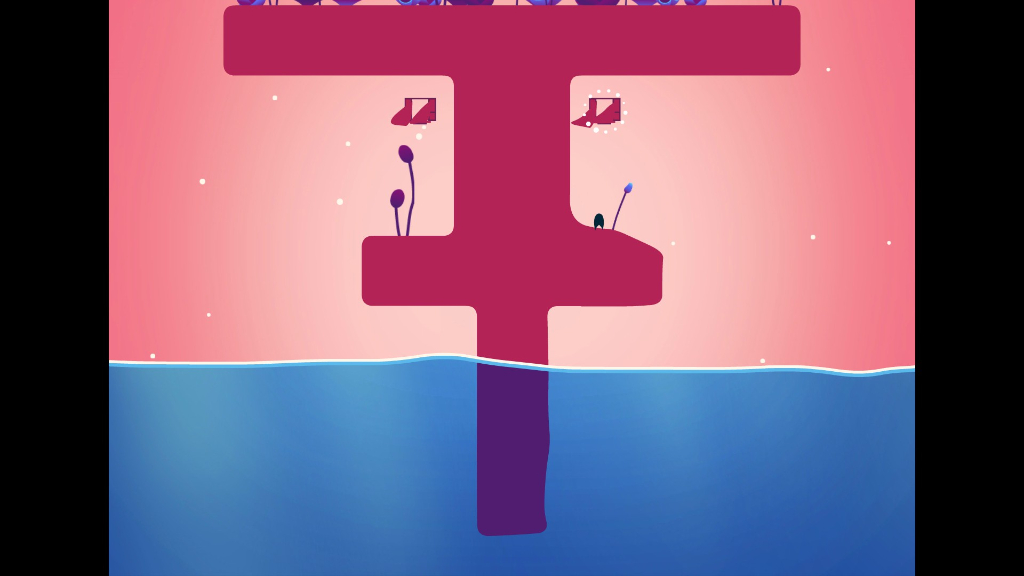

The Floor is Jelly blew us away when we reviewed, so it only seems fitting we sat down and talked with the mastermind behind it all, Ian Snyder, and spoke about everything from the game’s art direction to intentional “glitches” in the game’s climax. Over a few e-mails, we learned quite a lot about what inspired the game and its many distinctive facets.

What inspired The Floor is Jelly? Why a super-flexible physics platformer?

The game was originally a small prototype I made to distract myself from another game project that was frustrating me at the time. I liked the prototype better than the game I was working on, so I abandoned the game to finish the prototype.

Why did you go with a minimalistic art aesthetic and game world? Were there any artists or pieces that helped decide on the game’s look.

I’d argue that The Floor is Jelly takes little to no influence from Minimalism. You look at the work of someone like Donald Judd and it’s far, far, far away from TFIJ. You see a lot of starkness in minimalist works. Colors, if present, are often clearly delineated, forms are reduced to their most rudimentary, everything is 90 degree angles. A lot of Minimalism, quite honestly, leaves me cold. It works well when it’s trying to overwhelm you, when you feel as though somehow you’ve wandered into a parallel universe where everything is just platonic solids floating in a void, but that kind of feeling is obviously not what I wanted the player to experience in the game.

I think Minimalism gets thrown out a lot in talking about games when people are trying to say that a game is ‘simplistic’ without sounding derogatory. And, it’s true, TFIJ is more modest in its goals than some other games might be, but, again, I don’t feel the game is defined by reduction. It has many extraneous parts, little things tucked away inside the game that could ultimately be removed if we were just trying to represent only what “needed” be there. There’s a lot of clutter. Clutter is good. Clutter is human. I, as an author, am more present in clutter than in any other part of the game.

In terms of art direction, though, I was looking mostly towards Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Not, mind you, in the quality of brush strokes you might see in a Van Gogh – paint as a medium tends to speak more about dimensionality built up on a surface than flatscreen pixels do, brush strokes don’t manifest in digital works the same way they do in physical works – but more in the use of color. During the Post-Impressionism period especially, western fine art begins experimenting with non-literal uses of color in a really exciting way.

Otherwise, the aesthetic considerations of a painting are totally different than that of a game. Games have to build a certain symbology of reiterated images that all fit within a certain space to generate a specific set of potentialities and consequences, whereas painting does not. I feel that games are a lot closer to written word in that respect. So, often in development I’d run across some concept that I wanted to communicate about how the world worked to the player. For this, I really had to look at other games with a similar visual economy, and how they solved similar problems. Yoshi’s Island, Pixeljunk Eden, FEZ, Hohokum, Everyday Shooter, Loco Roco, etc.

There’s no real story to The Floor is Jelly, but you evoke a very particular tone and world. Was there any underlying theme you wanted to come across to the player as they explore the in-game world?

The game is not without a narrative arc. For one thing, there are bits of the game that qualify as story even by the most stringent definition, tucked away in secret corners, but even if the player never encounters these I think a distinct progression is apparent. We might consider the game as transpiring across three clearly delineated acts. The first is a period where the player learns how to control the character, and how to most efficiently move through the world. The second and third acts then expand upon these skills, but take them in opposite directions. The second act must occur after the first, as it focuses on expanding and refining the skills the player learned in the first act. Through the course of the second act, the player should move from “competent” to “skilled”. The third act must follow the second, as it stands counterpoint to the earlier lessons. The arc of the game, it’s thesis, emerges from the relationship of point and counterpoint. Each is incomplete without the other. Imagine encountering the final levels of the game without having played the earlier levels, their effect would be lesser. Similarly, if the earlier levels are not followed by the final set of levels, one might come away from the game with a totally different impression.

How was it working as a one man development team? Were there any surprises along the way?

Well, I wasn’t a one man team, for one thing. Rich Vreeland scored the game, and music is something that I see as totally integral to game design. It’s a significant part of the experience! Especially in levels such as rain, winter, or the water, where changes in music and subtle sound effects help to solidify concepts that are difficult to communicate through level design alone. It was helpful to have him to bounce ideas off of during the process of making the game.

How long over the course of development it take before all the game’s elements finally “clicked”?

It depends on which elements you’re talking about. Different things codified at different points. The physics were basically present in their final form from day one, but other things – secret areas, specific level designs, the overall tonal arc of the game, and so on – took longer. I was more or less tweaking different parts of the game all the way up to release, so I guess you could say it took the whole 2 years for everything to come together completely.

What was your favorite part of The Floor is Jelly?

I like the winter section a lot, but nothing tops the final section of the game for me.

Looking back, is there anything you might have done differently?

I wish I could have finished the game faster than I did, but I don’t know if, in that time, I was capable of working much faster. Certainly when I return to the game now I still see lots of little flaws in it, places I could have pushed further and done more with. Ah well, I can’t return to it now!

You’ve got a very fine-tuned sound and visual responsiveness in The Floor is Jelly. Grass turns into tall trees, luminous plants grow brighter with your actions, and gentle tunes waft in as you jump (and fall) through every level. Were these elements planned from the start or an extra sprinkling of interactivity along the way?

The plants you mention are actually a solution to a game design problem. They only appear in sections where the player may take one of multiple exits from a level, which led to players becoming lost since these window links don’t correspond to actual space. The plants that grow as you walk act as a trail of breadcrumbs, letting you know whether you’ve been in a place before.

Generally though, my creation process tends to be more intuitive. The best way I know to describe it is “listening” to the thing your making. It has set of desires, and my role is to find and fulfill them. You create a little seed, and something, you’re not quite sure what, says it needs to grow in this direction or shrink from that one. You do your best to follow the instructions, though they’re mostly inscrutable. Hopefully, in the end this leads us to a place where we can begin to make concrete, well-informed decisions about the thing we’re making. The players getting lost problem, for example, was only something that could have emerged via playtesting. Once you’ve created the foundation of your object, it’s more or less just seeking out and eliminating these rough spots until it feels like you want it to.

In the case of the music, we knew from the start that we wanted something more responsive to the player. We’d been talking a lot about David Kanaga’s work in game music, and Rich’s own music game January. From that point, it was really a question of how the music could best reflect whatever ideas a given level was trying to communicate.

How has the game’s reception been on Steam thus far?

Those who play it seem to enjoy it, which I’m glad to see.

What’s one piece of advice you’d give to anyone interested in solo-developing their own game?

One of the most important things you can do as a developer is to find a small group of people who you can trust for feedback that is both honest and well-considered. They don’t have to be game developers, they can be friends, family, artists in other fields, or anyone else, just so long as you find people you can trust. It’s easy to lose focus, get lost, or dig in too deep on a problem that doesn’t matter when you’re working totally alone, and seeing the game though someone else’s eyes helps to mitigate that.

Any hints as to what you might have planned for the future? You’ve mentioned on Twitter you are working on a 3D-engine with a sound focus.

Yes! That’s actually part of a collaboration with another developer. I’m mostly focusing on developing the tech that the game runs on, a change from my usual mode of working where I am the only person making every single element, while they’re handling game design, sound, graphics, etc. I’m working on a sound engine with a focus on spacialization, as one of our goals with the game is to give equal importance to visual and aural information.

Were the “glitches” planned or were they a result of, as you put it, “listening” to the game? In concept it would seem like they might clash with the design, but instead they fit amazingly well.

Most of it comes from the listening process, being attentive to what the game is doing as I’m making it. Perhaps it’s just because I find glitches inherently interesting of their own accord that I stop to examine them when they emerge in my own process. In the final section of the game, the majority of it is intentional in that I was purposefully pushing certain parts of the game until they broke. I knew the game’s engine well enough at that point that I had a good feel for what kind of glitches would emerge depending on where I took it. In that sense, they were both planned and emergent. They wouldn’t have existed if I’d gone through the game with a mind to eliminate every flaw completely.

For more on The Floor is Jelly, please be sure to read our review and visit the game’s website!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!