Madness has played a leading part in horror since long before the invention of digital entertainment, to the point where it has become a staple of the genre. Countless movies, books, themed attractions and campfire stories feature old standbys like haunted abandoned asylums, straight-jacketed inpatients screaming b***** murder at padded walls, and criminally insane convicts on the loose and armed with sharp objects and a vengeance. The portrayal of mental illness in horror games has followed eagerly in these ghastly footsteps, often quite successfully so – but is it time for a change of pace?

In video games past, insanity has been used in a myriad of ways. Character motivation, game mechanics, even entire settings – all at some point or another have been tied, for better or worse, in with some sort of mental illness. Many a madcap villain, for instance, has been explained away with little more than a “He’s nuts, okay?” and a shrug. Think Joker. Better yet, think Kefka.

Okay, so maybe Final Fantasy isn’t exactly horror, but Kefka’s scary enough all on his own to make my point. That’s a whole lot of crazy without a whole lot of explanation – and yes, it’s kind of fun to go head to head with a blatantly batty bad guy, but it’s also lazy character development. Worse, it perpetuates a damaging stereotype for the mentally ill, namely that mental illness and b***** mayhem go hand-in-hand. In fact, a mentally ill person is far more likely to be the victim than the perpetrator of a violent crime. All too often, however, video games cast enemies and protagonists alike as indefinably, randomly insane (sometimes via painfully lame plot twists) as a way of rationalizing extreme actions, as though mental instability is some sort of loopy one-way road to becoming a psychotic killer.

Then there’s the insanity game mechanic. Found in the Clock Tower franchise, the Amnesia games, Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem, and many more titles besides, it’s a trick of the trade that’s quickly becoming as familiar as more classic health bars and magic gauges. It’s not a bad trick, either; watching the protagonist unravel on-screen and being subjected to his or her increasingly awful hallucinations is a jarring experience, to say the least.

It is, however, a fairly one-dimensional treatment of what, in reality, is a serious and complicated situation. Dealing with a mental illness is nothing so straightforward as a simple balance between light and dark, and lighting a lantern to dispel the shadows is about as efficient a treatment for a mental meltdown as a lollipop for a broken leg. I don’t condemn the sanity meter entirely – it’s certainly an intriguing and useful mechanic, even if it is in danger of wearing out its welcome – but it would be more useful still to see a better-researched (or at least more intricate and original) variant take its place.

Then again, sometimes the horror isn’t strictly confined within the character’s mind. As the Mad Hatter put it in Alice: Madness Returns, “Madness is not a state of mind. Madness is a place.” In games like Alice and its sequel, the player character’s reality is warped or even shaped by the trappings of a troubled mind, and it is up to the protagonist to survive, or perhaps save, the very, very mad world into which they have stumbled. In Alice’s case, Wonderland and her own mental health are directly connected, and the salvation of one is the only way to fix, or at least improve, the other.

Though this treatment of mental illness has been criticized for casting mentally unstable protagonists as victims of their own damaged minds, I’d argue just the opposite is true. Heroes and heroines like Alice or Silent Hill 2’s James Sunderland may begin their respective quests as victims, but the whole point of playing their games is to learn how to navigate and overcome the perils of the personalized h**** into which these characters have been thrust. Alice and James confront their demons openly (and quite literally) in order to progress towards what will hopefully be a happier future. The point of fighting these battles isn’t to show how monstrous their problems are, but to prove that such monsters, no matter how terrifying, can be conquered.

However, not all horror game environments and enemies are so creative or enlightening. Despite being places of healing, asylums and hospitals have become a go-to location for crafting quick chills and thrills, as seen in popular titles like Outlast, Daylight, and of course, Senscape’s yet-to-be-released Asylum. The effectiveness is undeniable, and for one simple reason: we’ve taught ourselves, through repetition, to instinctively fear these settings, especially in horror games. Add to this the creep factor of any dark, abandoned building and an unhealthy dose of jump scares and bumps in the night, and it’s no wonder we find ourselves a little hesitant to set foot in such places.

The problem is how these games tend to treat these institutions – more specifically, their populations. Were Victorian-era (and earlier) sanitariums abjectly horrifying in their lack of humanity and modern medicinal knowledge? Definitely. Should we keep avoiding them like the plague? Nope; in fact, many (too many) people who would benefit from professional help steer clear of these institutions because of social stigmas and negative associations. Were the patients back in ye olden days any more violent, wild, or frightening than their contemporary counterparts? Of course not. People are people, and fact is, most of us aren’t mass murdering psychos.

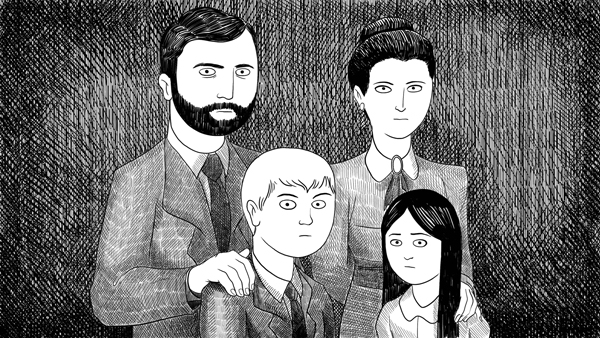

Time and again, however, horror games use patients like props in a haunted house, and they all look rather alike. The recipe is simple: take one straightjacket (secured or open, as you please) and apply to one scrawny, malnourished body scarred by self-harm attempts, add some Einstein hair, torn fingernails, and your choice of either bloodshot eyes or b*****, empty eye-sockets, and stir. Keep it stored in a dank, dirty cell, out of direct sunlight and away from children. Oh, sorry, did that sound grossly trite? That’s because it is. Ghosts other denizens of the paranormal ‘verse are one thing, but portraying human hospital patients as slobbering, rabid cannibals with no thought or want in life but to kill is something else entirely, and it’s not exactly a good something.

None of this is to say that video games are, or should be, the core of our moral compasses, or even that mental illness should never be portrayed negatively. Reality has had its share of crazed killers and sociopathic masterminds, and telling their tales and similar stories is far from taboo subject matter. That’s fine. The real issue is that there has been very little on the opposite end of the spectrum to balance out the negatives and dispel the illusion of the stereotypes – at least, until now.

The advent of the indie revolution brought with it a new wave of more mature, more personal storytelling in the vein of games like Braid and That Dragon, Cancer. Recently the trend has spread to horror games with the release of titles like Neverending Nightmares, inspired by developer Matt Gilgenbach’s struggles with OCD and depression, Nevermind, which uses biofeedback to adjust the difficulty and terror of the game to match the player’s stress levels, and semi-autobiographical interactive fictions like Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before and There Are Monsters Under Your Bed.

Developers took things another big step forward last year with Asylum Jam, a 48-hour game-making event focused on scary games and mental illness. The challenge was to create an original horror game which did not “use asylums, psychiatric institutes, medical professionals or violent/antipathic/insane patients as settings or triggers.” The inaugural 2013 jam resulted in interesting experiments in fear like Night Shift, Checkpoint-Z, Forest, and Tempus Fujit. (Asylum Jam is back for 2014, and will run from October 31st to November 2nd.)

Games like these don’t shy away from either horror or mental illness, but they do treat each with a much more human touch than the majority of their predecessors, and they prove that terror can coexist with empathy without losing any of its pulse-pounding effect. Best of all, these games highlight the real enemy: fear itself. Understanding is the only cure for our natural fear and hatred of the unknown, and the best way to turn the strange into the familiar is to walk a mile in its shoes. Knee-j*** aversions to asylum inpatients and mental illness are nothing more than learned responses, and it’s about time we started unlearning them.

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!