When one thinks of methods of teaching, scaring probably does not spring to mind. However, the team behind Nevermind aims to change that fact. By monitoring the player, the game will dynamically alter itself and become more difficult in order to teach stress management. Erin Reynolds is the Project Lead, Creative Director, Artist, and Designer for Nevermind and took some time from her busy schedule to answer some questions.

First off, how about some background on you specifically and your team?

I have been working within the games industry for over 10 years, primarily as a game designer, but also as a producer and an artist. I studied Fine Arts as an undergraduate student at USC and, after graduating and spending a few years in a professional setting, I returned to USC to pursue my MFA in Interactive Media so I could exploring the space of “positive games” and new, innovative technology.

As such, Nevermind was built as my Master’s thesis and, as part of that process, I had the immense privilege to work alongside a rockstar student team throughout an academic year. The team was made up of Computer Science, Electrical Engineering, Cinema, Interactive Media, and Music students. Everyone brought their unique ideas and perspective to Nevermind and made it into what it is today. While the current team is much smaller, I’m looking forward to bringing on as much of the original team as I can (along with some industry veterans who are eager to jump on board) as soon as we get funding to move onto the next phase of Nevermind’s development.

For those who have not heard of your game what is Nevermind?

Nevermind is a biofeedback-enhanced adventure horror game that takes you into the dark and twisted world of the subconscious minds of psychological trauma patients.

As you explore surreal labyrinths and solve the puzzles of the mind, a biofeeback sensor (currently a Garmin cardio chest strap and ANT+ USB stick) will monitor how scared or stressed you become moment-to-moment. As you get more scared or stressed, the game will respond by becoming harder. However, if you’re able to calm yourself in the face of terror, the game will return to its easier, default state.

Although we built Nevermind first and foremost to be an incredibly fun game, it was also important to us that Nevermind would challenge the player, leaving them braver and more confident than he/she was going into the experience.

The big picture idea for Nevermind is that, by forcing you to confront stressful and uncomfortable situations and learn how to manage your internal reaction to them, it teaches you how to be more mindful and aware of your responses to stressful situations. In other words, if you can learn to control your anxiety within the disturbing environments and scenarios throughout Nevermind, just imagine what you can do when it you unexpectedly face those inevitable stress triggers in the real world.

Could you provide an example of the game directly reacting to the biofeedback?

In the current version of Nevermind, the environment dynamically responds to the player’s anxiety levels.

One of my favorite examples of an environmental response occurs in the “kitchen” area of the current level. If the player starts to get scared or stressed while in the Kitchen, milk will start to pour out of things like the toaster or cupboards (I know it sounds strange – but trust me, it makes sense within the context of the narrative).

The longer the player stays stressed or scared, the more the room will flood with the milk. Initially, the milk just impairs the player’s ability to walk – since he now is slowed down by having to slosh through the liquid-y room. If the player doesn’t calm down in time, the milk will eventually cover his line of sight – making it impossible to see the space around him. Eventually, if the player stays too anxious for too long, the milk will essentially “drown” him.

In Nevermind, death and game-overs are treated a little bit differently than they are in many other games. In the case of the milk, for example, drowning is just the Nevermind’s way of sensing that the player is getting too stressed out. As a result, the player is taken out of the Kitchen and placed in a calmer part of the level. Once the player is able to recover and gather himself, he can then return to the Kitchen and pick up where he left off. Of course, if the player is able to successfully calm down before getting to the point of drowning, the milk will simply drain out of the room and he can proceed normally.

What sets it apart from what is currently on the market?

Having a game respond to your internal state creates a whole new level of immersion that we have yet to see in most, if not any, games currently out there. Not only does the biofeedback technology set it apart, but the narratively rich and gameplay dependent aspect of that technology’s integration adds a dimension to biofeedback that has yet to be seen.

Beyond that, as noted earlier, Nevermind is also relatively unique in that it strives not only to entertain but also benefit the player. The use of biofeedback and the rise of positive games (games that are entertaining and beneficial) are both emerging trends that are only going to become more prominent in the next few years. However, for the time being, Nevermind is a fairly unique instance of both.

What was the inspiration behind creating something so different?

I’ve always been passionate about positive games and have made it a focus of my career for the past five years. Furthermore, new “listening” technologies like biofeedback are a natural fit with games that can help the player in deeper, more powerful new ways. Plus, I’m a bit of a geek and, after having gotten a small taste of the potential of biofeedback in gaming on an earlier project, I couldn’t wait to dive into it fully when it came time to put together my thesis project.

Did you approach any publishers or just decide to be indie from the beginning?

Since Nevermind started as a student thesis project, it was inherently indie from the get go. That said, given its experimental nature, I think going indie from the outset made a ton sense for Nevermind regardless. I love the indie scene and all the wild, creative energy within the community!

Right now, we’re just focused on making sure that the full vision of Nevermind can be realized – that is, taking it from its current academic version to a full, releasable version. So at this point, whether that means we do so via publishers or the indie route simply depends on whichever option makes the most sense for enabling that. Currently we’re exploring everything!

What is biofeedback?

Simply put, biofeedback is an external entity’s response to a person’s internal state. In the case of Nevermind, it’s the game’s response to the player’s psychological arousal (i.e. fear or stress) as derived from an over-the-counter cardio chest strap.

Are there any other games that use biofeedback or is Nevermind the first?

Nevermind is definitely one of the first, if not the only, game of its kind to leverage biofeedback within a “traditional” game setting. While there are many great applications that use biofeedback, many of them are really more exercise/meditative app variants than fully fledged games. Both types of products are very valuable, though, and we’ll certainly be seeing more games and helpful apps that use biofeedback input out on the market over the next several years.

How are you monitoring it as the player plays?

Nevermind currently uses a Garmin Cardio Chest Strap and ANT+ USB stick to gather data on a player’s heart rate as they play the game. From there, the game can determine a player’s Heart Rate Variability (HRV). HRV is a wonderful way to determine if someone is getting scared or stressed and it’s ultimately the primary metric we look at when determining a player’s internal state.

What will you specifically be monitoring?

As mentioned in the previous question, we primarily monitor Heart Rate Variability via the biofeedback sensor. However, if someone plays Nevermind without a sensor (which is completely fine), we look at other signals such as mouse movement and button press frequency to approximate their fear or stress levels – with the idea that if someone is button mashing or moving the mouse around erratically, they’re starting to get a little anxious.

Do you think biofeedback has a future in gaming and could lead to unique and interesting experiences?

Absolutely! I have no doubt in my mind that biofeedback will be an expected component of games and technology in the future. Biofeedback not only offers a new level of immersion, engagement, and intimacy with a game, it also creates a bridge between gaming and important areas like health, education, and communication. I couldn’t be more excited about the future!

The game currently has four areas correct?

The game currently has one full level (i.e. one trauma patient) and the “hub” area for several future levels (which would be new and different trauma patients). That said, the patient’s mind is a broad and diverse experience that includes a variety of different areas (closer to 10!). For context, playing through the current “phase 1” version of the game tends to be about an hour long experience.

Where there any direct inspirations to any of the environments and what is contained in each one?

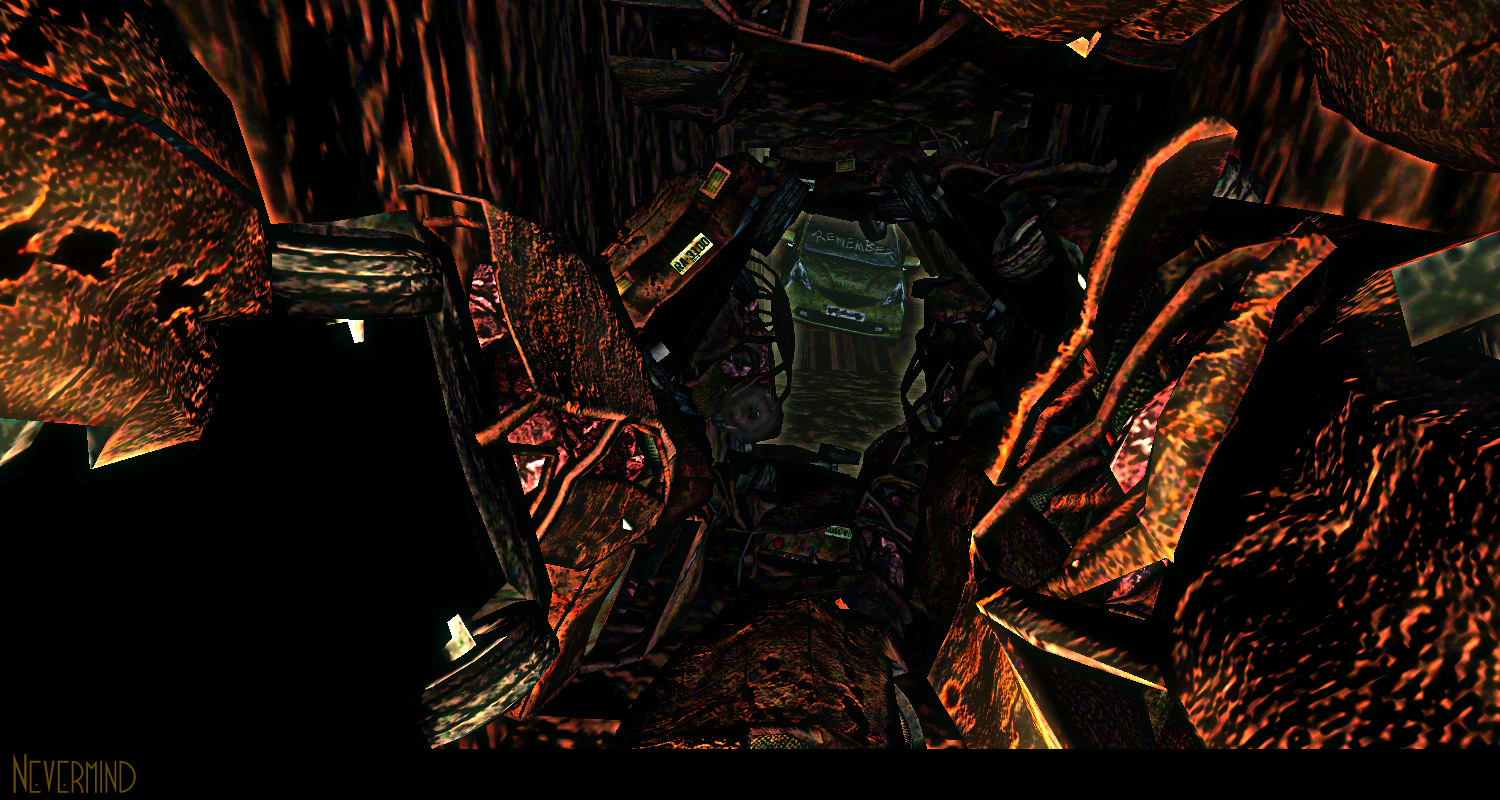

Every detail within the level is a clue to the mystery that you’re trying to solve. To provide a little background on the narrative of the game, in Nevermind, you take on the role of a “Neuroprober” – a psychiatrist of the future who can delve inside the subconscious minds of extreme psychological trauma victims. These are individuals who experienced something so heinous that their conscious mind couldn’t handle the memories of the event. As such, they have no way of recalling what it was that happened to them and, in some cases, that anything occurred at all.

However, the subconscious mind still knows that something is terribly wrong and, consequentially, twists and churns over the fragmented memories – trying to figure out what happened. As a result, although the victim can’t recall the details of the event, it still impacts their life in a variety of negative ways – such as interfering with their ability to hold a steady job or maintain healthy relationships. This aspect of the Nevermind narrative is actually based on what can happen to psychological trauma victims in the “real world.”

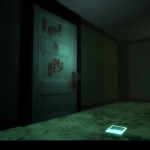

One therapeutic technique to help those trauma victims is to confront them with the memory – if they can recognize it and own it, then they have something that they can work toward resolving. In Nevermind, you must first uncover what that memory is by exploring every nook and cranny within the victim’s mind. Buried within the patient’s subconscious are ten photographs – each representing a possible fragment of the original memory of the trauma. Five actually show a facet of the traumatic event and five are “red herrings,” that is, false memories – the product of years of the subconscious psyche’s attempts to cope with the trauma itself. By the time you have collected all ten photographs, you will have seen enough clues to be able to determine which five photos pertain to the trauma event and in which order they occurred. It is important to note that everything is a clue – from the environment, to the photographs themselves, to puzzles you need to solve, to even the biofeedback reactions. Once the right five photos and placed in the right order, the memory is unlocked and the victim can now, finally start on a path toward healing. In Nevermind, each level is a different patient and different trauma – opening the door to investigate the breadth and complexity of psychological trauma and PTSD from an entirely new perspective.

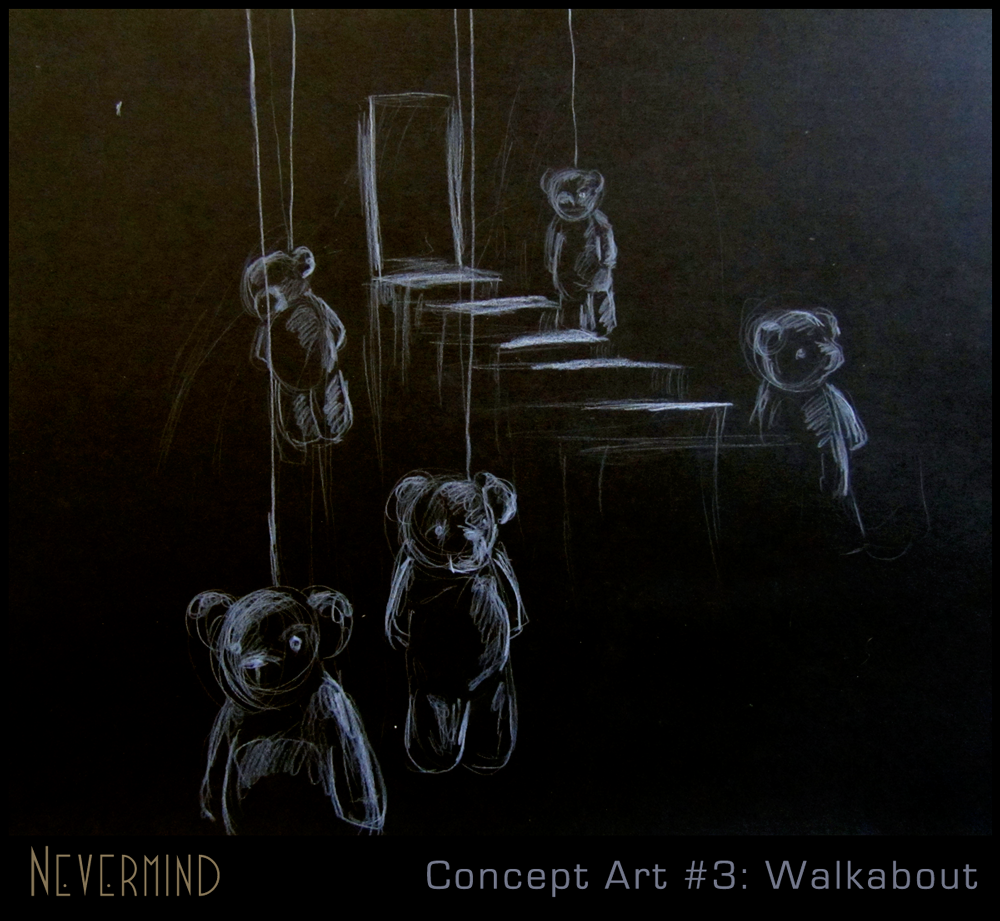

A lot of what I have seen about the game is extremely surreal. What are the intentions for having such surreal imagery?

We wanted the type of “horror” in Nevermind to be of the atmospheric and uncanny kind – the kind that gives you the feeling that something just isn’t right. As such, we swapped the use of jump scares, gore, and monsters found in many traditional horror games for dark, surreal imagery that is intended to affect the player on a very psychological level. For this we referenced film, fine art, books, music, and other games for inspiration in how to create a truly unforgettable world.

What are some of your favorite horror games, movies, and/or books?

I’ve always been a huge fan of horror! I practically worshipped “The X-Files” and “Millennium” back in the day, one of my favorite games is “Eternal Darkness,” and I love the writings of H.P. Lovecraft. As a little known fact, I used to live just 15 minutes away from many of his old “haunts,” and whenever I visit home, I usually spend a day to take the official H.P. Lovecraft walking tour.

What about them made them memorable and scare the player, reader, viewer?

One theme that I have always been drawn to and, in many ways, have incorporated into Nevermind is the fact that the greatest monster is almost always the one within. To me, there is something that is both incredibly terrifying and empowering about that notion.

Have any of these influenced the creation or content of Nevermind?

They’ve inspired much of my work and, no doubt, have influenced the creative direction of Nevermind.

What are your thoughts on the current states of horror games?

I love horror games and admire many of the ones currently out there! With that being said, I’ve often found myself frustrated with how mercilessly punishing many of them are (both modern day games and the classics). There are so many games that, although I’m a pretty seasoned gamer, I just couldn’t get more than 20% of the way through. As such, I ultimately ended up missing out a lot of fantastic content. Granted, I understand and appreciate the merits of a fiercely challenging game. Nonetheless, it bums me out when I don’t get to experience everything a game has to offer as a result.

I wanted Nevermind to be a game that both hardcore gamers and complete non-gamers alike could enjoy. As such, I shifted the challenge away from being based on twitch reactions and brute force to more of “Myst”-like structure of puzzle solving and exploration – and, of course, demanding that the player wrestle with their own internal stress reactions.

I am saddened to see the Kickstarter failed to reach its goals. What are your current plans moving forward?

Although the Kickstarter didn’t end up getting funded, we feel that it was still a great success! We have been absolutely overwhelmed, inspired, and encouraged by the massively positive response it received from gamers, press, and medical community. We’re determined to make Nevermind a reality and are currently exploring a number of very exciting possibilities for the next few steps.

Can we expect another Kickstarter once some more anticipation has been built up?

That’s certainly one of the options we’re currently exploring – we’ll have more to share in the next few weeks!

Is there any way people can still donate or support the game?

We’ll have more actionable ways to help support the game in the near future, but for now, the best way that those who want to see Nevermind get made can help out is to sign up for our mailing list, follow us on social media, and continue to share their excitement and enthusiasm with others!

Any closing comments?

Stay tuned for announcement on exciting developments in (hopefully) the coming weeks! We’ll be keeping everyone posted on our next few steps via our website (www.nevermindgame.com), Facebook page (www.facebook.com/NevermindGame), Twitter (@NevermindGame), and mailing list (http://eepurl.com/GiLib).

Also make sure to check out the Kickstarter page

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/reynoldsphobia/nevermind-a-biofeedback-horror-adventure-game

for some playthroughs of the game and even more information about the game.

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!