Every longtime gamer has at least one. Even if it’s not sitting on the shelf anymore – sold in a garage sale, perhaps, or lent to a friend who still swears it’s around the house somewhere – it’s been preserved, in the original packaging, of course, in the digital library of your heart: an old game that you never quite forgot. It might be a little dusty, and maybe a little worse for wear after a few decades of neglect; heck, you might not be able to remember most of it anymore, or even have a clear idea of why you liked it in the first place. But for whatever reason, it stuck with you.

One day something reminds you of it; a meme referencing a funny bit of dialogue, a retro poster hanging in a store window, or a bargain bin action figure missing an iconic weapon but still in pretty good shape for its obvious age. And suddenly there it is: that craving to revisit the past, a surprise attack of nostalgia that compels you to check those old boxes you never got around to unpacking, just to see if maybe you still own a playable copy. You never know. If you don’t, you might be able to buy a new (or used) copy online, though depending on how rare it is, it might cost you a pretty penny. Don’t forget you also need a compatible console. Don’t have one? Well, you could always go look for an emulator, or a YouTube walkthrough – but it’s not really the same, is it?

Truth is, even if you have everything you need to play that game, it probably won’t be the same as you remember anyway. Video games are a special kind of art which weathers the passage of time rather badly, and few can stand the test of time for more than a decade or so, if that. It’s not that they turn rotten after a certain amount of time like a bowl of fruit, but with game tech progressing so much and so quickly, it’s hard to be wowed by the “cutting-edge” graphics of, say, 2004, once you’ve seen what developers can do in 2014.

This is where remakes come in. While ports preserve the past in all its original glory, a good video game remake can bring an old classic back to life with enough updates and new tools to survive alongside the recent hits – for the time being, at least. A remake can also polish up a diamond in a rough, a long-forgotten gem with untapped potential just waiting to be redone right. Remaking something is the art of balancing preservation with rejuvenation. When it’s good, it can be very, very good. And when it’s bad… well, you know.

Of course, not every video game needs to be remade. Just look at Hollywood; nine out of every ten “re-imaginings” and “reboots” flooding the theaters are utterly unnecessary and unwanted. Some bad movies just can’t be fixed, and most good movies don’t need fixing in the first place. Thankfully, the gaming scene isn’t as glutted with revitalized garbage the way the big screen is, but the basic principle is the same. Some games which practically beg to be remade are ignored, while others might get superfluous facelifts that end up being as frustratingly worthless as a Botox injection.

So what’s the difference? What makes a game worth a remake? While any set of rules would inevitably be subjective and up for debate, I’ve done my best to isolate and refine the most important remake/reboot/re-whatever prerequisites, which should be applicable to any given game. (If you happen to be a developer considering remaking a game yourself, you might want to start taking notes. Don’t worry, it’s a short list.)

#1: The game should be at least five years old.

Preferably ten or more. But seriously, if it came out yesterday, what’s the point? Give it some time to marinade. Maybe it’ll get better over time, like fine wine, and thus no longer require a remake. Or maybe it’ll disappear completely from the public eye, most likely for good reason, at which point it will become ripe for a revisit. Just don’t try to convince people to buy a new version of a bad game they wasted good money on only last year; it’s basically rubbing salt in an open wound.

#2. The game should be one the developer is intimately familiar with.

Like rule #1, this is more prescriptive than absolute. But the best remakes almost always reflect a deep understanding of the source material, an intimacy situated somewhere between blind adoration and abject loathing. That sounds a little extreme, but in order to do a good job, the developer should care enough to love (and therefore effectively preserve or enhance) the best core elements of the original, yet also be able to turn a critical enough eye on it to recognize what didn’t work the first time around and what needs to be either changed, updated, or eliminated entirely in the new version. Though technically a reboot, Doom 3 is still a fair example of this. In addition to being a vast aesthetic (and, quite frankly, narrative) improvement on the ’90s hit franchise, it remains unquestionably a Doom game thanks to the company’s decision to keep the same claustrophobic atmosphere, high-powered weaponry, and horrifying monsters which drew gamers to the original in the first place.

#3. The game must be significantly lacking in some area, or would greatly benefit from new advances in technology or design.

Or, to put it another way, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” In order to necessitate a remake, a game must be in need of some sort of improvement, either because it has become dated or because it had problems. Otherwise, it’s like remodeling an already picture-perfect room: senselessly expensive and ridiculously time-consuming.

Furthermore, the game element in need of work must be (a) an important element which is (b) obviously in need of some TLC. In other words, if the only issue is that the controls are slightly wonky at times, or there’s a weird glitch that only happens when the player tries to scale a cliff wall on horseback, we don’t really need a whole new game. Just make a patch, or better yet, get over it. But if, for example, the “realistic” graphics look like an arcade cabinet’s nightmare, or the combat is so broken it’s barely playable, it might be time for a makeover.

Similarly, if technological (or financial) restrictions at the time of the first release kept the game from including elements which would vastly enhance either the gameplay or narrative, this might be grounds for qualification as well. Transforming 2-D into 3-D, adding co-op or multiplayer modes, and inserting new or improved voice acting are the most common examples.

Another possibility that would qualify a game under this rule would be if the original game is missing important information that would be difficult, if not impossible, for a new generation of players to access. While a mere port would do nothing to rectify this, a remake could flip the rulebook entirely or, at least, alter the main menu to include the necessary instructions. A perfect example of this is Super Metroid, which was ported to the Wii U last year. The problem? Like many older games, the original instructions were included in the game manual (which, obviously, didn’t come with the port), not in the game itself. Veterans of the series didn’t need no stinkin’ instruction manuals, but newcomers hadn’t a clue. Needless to say, the help forums exploded shortly thereafter.

#4. The game must have potential.

This is probably the most subjective rule, but also the most vital. While a challenge may be tempting, if there is no possibility of redemption for a game whatsoever (think Ethnic Cleansing or Postal 2), it’s best to let the dead rest in peace – or pieces – and move on to something that might actually work. Of course, being able to tell whether something has potential or not can be a tricky thing. One guideline might be the game’s popularity; if sales were high during its heyday, or if people are still searching for and talking about it now, chances are good a new-and-improved version will be welcome. Since popularity does not necessarily equal quality, however, oftentimes the best course is to have a good, long think about what it is that made you want to give that game the gift of rebirth in the first place. Were the characters iconic? Did the humorous dialogue make you laugh out loud? Did you fall in love with the world or long to see more of it? If the reason is trite, has limited applicability (i.e. is rooted in personal reasons or inside jokes), or unlikely to carry over well to the new version, drop it.

While certainly not the only quality that might motivate someone to become the next video game Re-Animator, story is, arguably, the best and most important indicator of whether a game should get another go. After all, the narrative (a good one, anyway) is the most durable element of any game, and the least likely to become outdated later down the line.

Take Clive Barker’s Undying. Though it came out thirteen years ago, I still remember the shock of the twist ending, and the journal that came with it still sits on my bookshelf, with pages well-worn from frequent reading. I tried to replay it not long ago, but next to the mind-blowing sorcery at developers’ fingertips these days, the graphics and combat feel pretty cringe-worthy in comparison. It’s still a good game, but that doesn’t change the fact that I would, if necessary, sell my (or someone else’s) soul for a remake. Why? Because the Covenant family haunts my dreams to this day. Because even over a decade later, I continue to love it. And because it’s a story worth telling… and retelling.

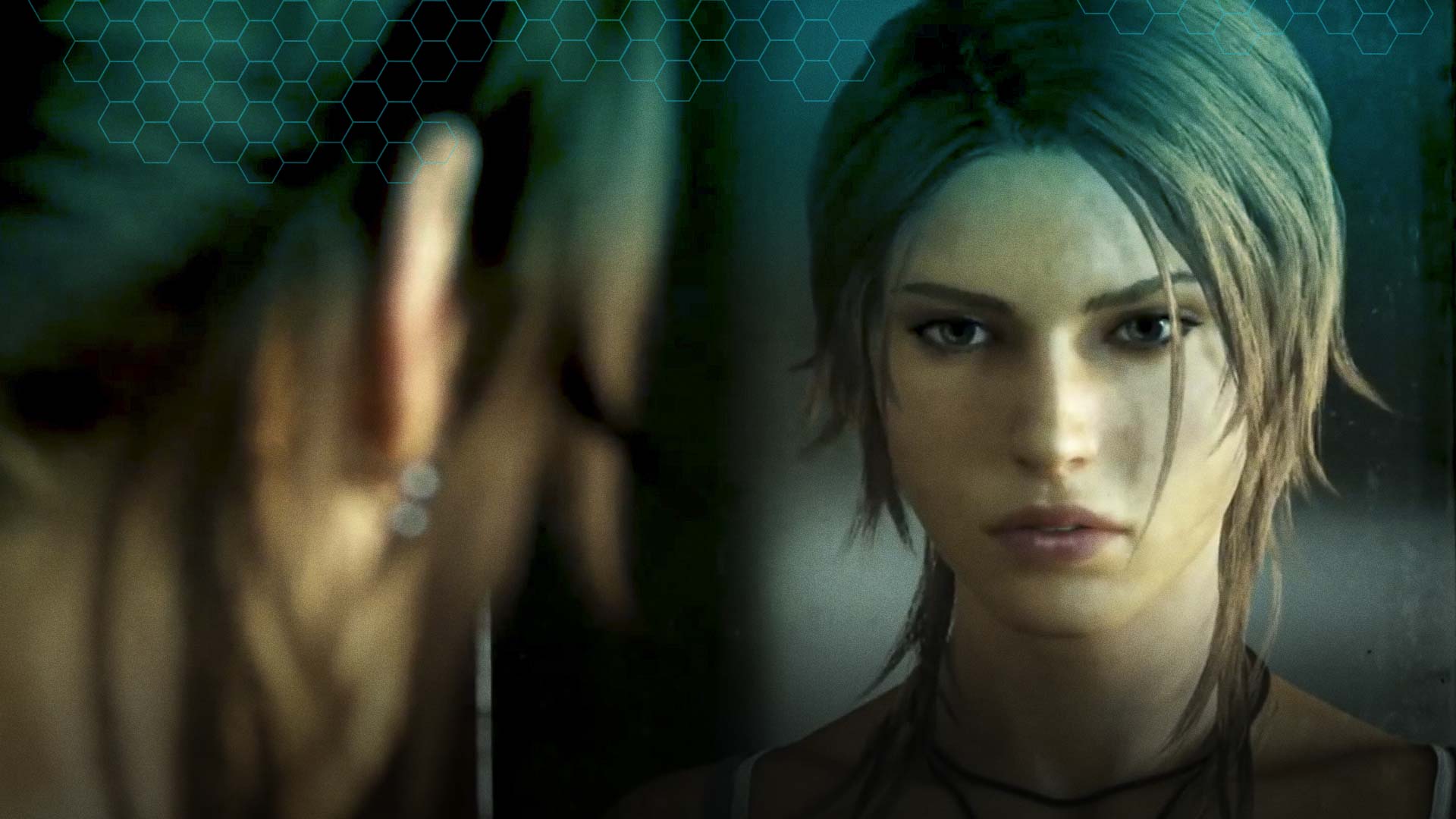

So, to return to our original question: which games really merit do-overs? The shortest of short answers is, games worth remembering. While remakes tend to be made by, and for, the people who loved the originals, they are also for posterity, for the new kids on the block as well as the old neighbors who just never got a chance to check out the classic version. The primary focus of the industry as a whole should be invention and originality, of course; relying on past successes like a crutch would be a deadly mistake. (Again, look at Hollywood. Better yet, don’t.) But some relics of the past are worth preserving, and it is these games that most require, and deserve, a second chance. Just ask Lara Croft.

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!