Previously on “A History of Imaginative Gaming“, we followed the eloquent footsteps of text adventure pioneers through colossal cave systems and traveled back in time to the age of 8-bit worlds and hand-drawn sprites. Now, it’s time for the other half of the story, which should lead us back, at last, to the present – provided we don’t get lost in the “maze of twisty little passages, all alike” along the way.

Once again, the exact chronology is elusive at best; “art games” weren’t even referred to as such until a paper published in 2002 despite origins reaching back as far as the 1970s, and the title and release date of Japan’s first visual novel (or VN) is pretty much anyone’s guess. We do, however, have one particular landmark to point to, dated 1983…

More than Meets the Eye: VNs

The popular perception that visual novels are all either dating simulations and/or hentai (that is, p***) is an unfortunate and unfair generalization of a genre as capable of variety and complexity as any other. That being said, I would be a liar if I didn’t admit that many of the earliest known VNs were, in fact, of the creepy/erotic type, so bad the titles alone are NSFW. I leave it to the recklessly curious to google these for themselves, at their own risk.

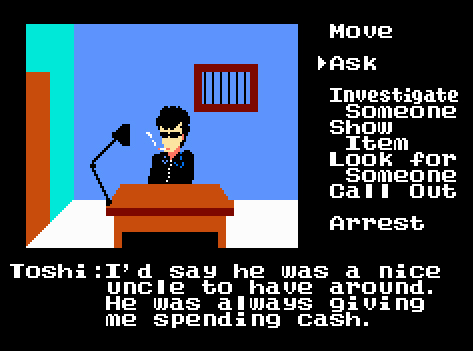

For the rest of us, things didn’t get properly interesting until 1983, with the publication of Chunsoft’s The Portopia Serial Murder Case, touted by Square Enix as the world’s first true detective adventure game. It required players to catch a serial killer by collecting clues, questioning suspects, and solving puzzles, with several possible narrative branches and a shocking twist at the end. At the time it sold over 700,000 copies for the NES, and is often cited as one of the first influential VNs ever to be released.

The next step in the evolution of this particular brand of imaginative gaming came nine years later with ELF’s Dōkyūsei (literally, Classmates). Featuring slightly lighter subject matter than Portopia, Dōkyūsei was the first adult dating sim. The story, to the extent that there was one at all, revolved around a male student’s last high school summer vacation. One of several female romantic interests could be pursued at a time, with the player working towards happily ever after by interacting with the chosen girl as often (and as skillfully) as possible. Though not all VNs are dating sims, they became (and remain) one of the most popular subsets of the genre.

1992 also witnessed another Chunsoft game, entitled Otogirisō, or St. John’s Wort. Unlike Dōkyūsei’s fairly simple story, Otogirisō presented a complex, well-written narrative with multiple possible endings. It embodied terrifying gameplay long before survival horror became popular, and introduced a new term: “sound novel.” Though originally there was (ostensibly) a fine but definite line between sound and visual novels, in practice the two quickly became synonymous.

When Chunsoft released Otogirisō, it trademarked the phrase “sound novel” as its own. However, that particular style of storytelling was too successful (at least in Japan) to be ignored by competition, so in 1996, Leaf found a way around the trademark by releasing the first game to be marketed as an adult-themed “visual novel,” Shizuku (literally, Drip). It was also the first VN to use character sprites, which would become characteristic of the genre thereafter.

In 1997, To Heart, the third and final installment in the “Leaf Visual Novel Trilogy” following Shizuku and Kizuato, hit the market. To Heart is widely credited for cementing the tone and format of all the VN releases which followed (dating sims in particular). While the previous games tended towards darker, serious themes, Leaf took a lighthearted approach with To Heart, adding a comedic touch and ten possible love interests.

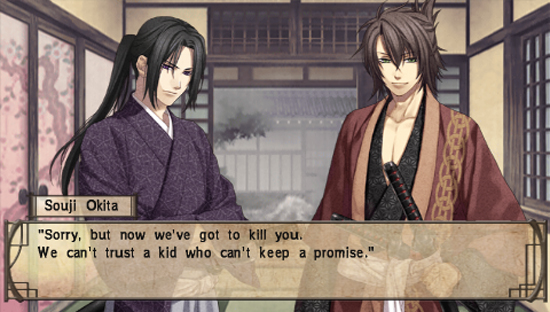

In Japan, enthusiasm for VNs is as strong as ever. In contrast, the majority of US releases seem to be either cheap fangames or fan-translated bootlegs, and despite a slow but steady growth of online demand, official VN releases in America are precious few and far between, even with US-based indie studios like sakevisual and Winter Wolves doing their part to spread the love. There is, however, hope for the future: several official English localizations, such as Ace Attorney, Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward, Hakuōki: Demon of the Fleeting Blossom, and Catherine, were well-received in America and won both awards and high ratings, proving such games have real market potential here as well as in Japan.

Painting with Pixels: Art Games

The most controversially-named genre of pretty much anything ever, it is highly debated whether “art games” should be considered a separate category at all. Some argue that all games are art, and separating a few under such a heading implies false superiority; others believe no games are art, and so-called art games can be either video games or art pieces, but not both. A possible alternative name is “experimental games” – however, I find this phrase tends to conjure up images of scientists in lab coats conducting psychological experiments on players hooked up to hulking towers of high-tech machinery. For now, for lack of a better word, let’s stick with “art games.”

What is an art game? In this article, the term refers to any video game developed with artistic intent (as opposed to gameplay, combat, etc.) as the primary, if not sole, focus and purpose. Artistic intent in this case includes conveying a meaningful message, exploring and experimenting with game design and player-game interactivity, and raising thought-provoking questions which go well beyond the borders of the in-game world. That is, of course, not to say that only art games incorporate these elements; the difference is simply one of emphasis.

For example, The Game of Life (or, simply, Life) was a zero-player game created by John Horton Conway in 1970 in which a handful of mathematical rules provide the basis for life and death. The player determines the initial conditions, populating a given set of cells in (hopefully) an optimal configuration, and then sits back and watches evolution take over. Much more than a mathematical exercise, Life presented an abstracted commentary on the survival of the human race: like the cells, if there are too few of us, we peter out of existence; if there are too many, we overpopulate ourselves to death.

In 1982, another interesting specimen appeared in the form of Bernie DeKoven and Jaron Lanier’s Alien Garden. The game cast the player as an insect in – you guessed it – an extraterrestrial garden, which, thanks to randomly generated conditions, appeared differently on each playthrough. At a time when most major releases involved large-scale combat, Alien Garden offered a refreshingly peaceful alternative. (Except, of course, when flowers in the garden exploded. In the words of the game manual, “Then you are dead.”)

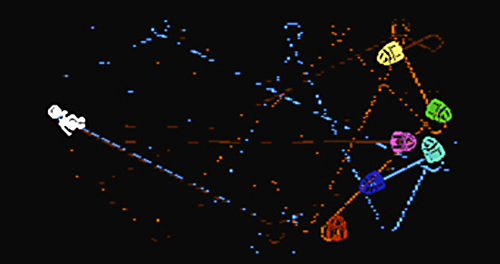

The following year witnessed the release of what is often called the first true art game. Another Jaron Lanier creation, Moondust invited players not just to beat a video game but to experience it. The player controlled an astronaut whose prismatic vapor trails could destroy enemy ships and whose movements directly affected the tone and pace of the ambient score. The combination of flowing colors and interactive music created one atmospheric (read: trippy) experience. Fun fact: it was around this time that video games began appearing in museum exhibitions like Corocan’s ARTcade in 1983. Moondust has appeared in numerous exhibits over the years.

By the 90s, artists with little or no prior experience in video game development began testing the waters, resulting in what some call “artist games,” like Trigger Happy (1998), which put a philosophical spin on classic Space Invaders-type arcade shooters. Not long after came the “art mods,” modifications of preexisting games which cast the content in a new light, sometimes expanding on, other times criticizing, various elements of the original. 1983’s Castle Smurfenstein, for instance, parodied the original Castle Wolfenstein by replacing N**** with Smurfs, while the Counter-Strike mod Velvet-Strike (2002) responded to then-President George W. Bush’s so-called “War on Terrorism” campaign by arming players with the tools to create in-game anti-violence graffiti art.

Today, art games seem to be gaining both more recognition and more fans than ever before (especially in the indie scene), judging by the recent success of titles like thatgamecompany’s Journey, The Chinese Room’s Dear Esther, and Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero. This may be due in part to the general rise of the indie scene itself – or perhaps gamers are simply craving something a little different to balance out the mass production of hastily-developed action titles which flood through the mainstream gates every year.

TBA: The Future of Imaginative Gaming

Now that we are back in the present, the question inevitably asked is, “What next?” Will the popularity of retrogaming and art games continue to rise? Will interactive fiction make a surprise mainstream comeback someday? Will visual novels ever make it big outside of Japan?

Though fame and fortune are often fleeting and near-impossible to predict, the staying power of all four of the genres discussed suggests imaginative gaming is here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future. With any luck, and if recent successes are any indication, it might even one day break the current mainstream mold. In the meantime, we must be content to cross our fingers and keep an eye out for upcoming releases like Jonathan Blow’s The Witness (set to come out later this year), The Chinese Room’s Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (currently set for 2015), and Circle Entertainment’s English localization of Harvest December, which was announced earlier this year and has yet to receive a US release date.

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!