With augmented reality slowly worming its way into our daily lives and virtual reality headsets like the Oculus Rift looming on the horizon, it seems more and more likely that the face of technology, and especially that of video games, is going to continue to transform and progress at a miraculous rate. But what about the faces of gaming – the heroes we spend uncountable hours fighting side-by-side with to save world after world from impending doom? Or, for gamers with a slightly more sinful bent, the villains we co-conspire with to tear those same worlds apart? What happens to our connection with them when the virtual-reality lines begin to blur and gaming gets real?

As it is, current video games have already been pushing and twisting these boundaries for years. When talking about the experience of playing a game, people often say things like, “I found all the secret rooms,” or, “It only took me two tries to beat the final boss.” But when referring to plot points, cut scenes, or other gameplay elements outside of the player’s control, often the subject switches to the game’s protagonist, as in, “Harry is really clumsy,” or, “I cried when Alice found the White Rabbit.” What causes these distinctions, and why is it they don’t seem to apply as much to games like Slender: The Eight Pages or The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim?

Working within the restrictions of presently-available technology, player-character relationships are mainly affected by three elements: camera perspective, character type, and the extent to which the player is able to interact with and, more importantly, impact in-game environments and events. Each of these elements, in turn, has multiple facets; configuring these to the greatest advantage for the sake of both gameplay and story is one of the most important responsibilities of any game developer.

There are three basic types of perspective in video games: third-person omniscient (PONG, Civilization, The Sims), third-person limited (Pac-Man, Resident Evil, Heavy Rain), and first-person (Spasism, Call of Duty, Dear Esther). Third-person puts more distance, both physically and mentally, between the player and the character. Omniscient is the most detached version, casting the player as a presence akin to a god, all-powerful but completely separate and other compared to the rest of a game’s populace. Third-person limited narrows the focus to a single character or small group, creating a stronger, though still slightly detached, link – a sense of camaraderie, as though player and character(s) are cooperating to achieve the same end. First-person, of course, further intensifies the connection, creating a sense of oneness with the character which may even exceed solidarity to the point of the player becoming the character, depending on what type of hero the protagonist is.

The “type” of hero, in this case, refers to how much personality he or she has. A developed protagonist is imbued with an obvious and wholly separate identity from the player, which can be expressed through dialogue, physical appearances, mannerisms, and actions beyond the player’s control. This distinction is often favored when a game’s story is largely character-driven, as developers are free to create a character with a high level of detail, both externally and internally. Most of the gaming world’s most memorable faces, like Harry Mason, Lara Croft, and the keyblade-wielding Sora, all hail from this category. In these cases, the relationship between player and character involves an odd balance between the independent agency and cooperation of two separate beings controlling the same body.

On the other hand, a silent protagonist with an unexpressed or undeveloped personality functions less as a companion and more as a blank slate for the player to project an identity onto. Instead of fellowship, the relationship here is much more visceral. Rather than feeling sympathy for the hero’s plight, the player feels that he or she is the hero, with the result being that the rewards – as well as the dangers – seem that much more immediate and personal.

Such characters may be given their own name and possibly their own face, like Half-Life’s Gordon Freeman, but because these small discrepancies appear only rarely in-game and no external personality is associated with them, the product is often a near-seamless sort of player-character unity. The ultimate example of this type is the silent protagonist found in Myst. Known only as The Stranger, this hero’s face and backstory remain unsolved mysteries, and his or her in-game actions are dictated almost solely by the player.

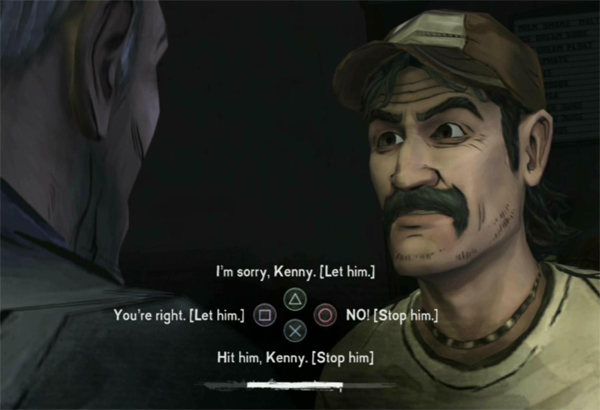

Finally, the extent to which a player can impact their surroundings and future events also affects how close they feel to their in-game avatar. Generally, the more agency and influence a player has, the more deeply connected they are to in-game events – and, by extension, the person on the screen experiencing those events. In Amnesia: The Dark Descent and, to a slightly lesser extent, its sequel, high levels of environmental interactivity worked to convince players of their own in-game presence. Meanwhile, in the episodic Walking Dead series, players often face difficult and complicated decisions, and every course of action has its ramifications. This combination of choice and consequence is a different means of achieving the same result: convincing the player that they exist within the virtual world, by giving their actions significance beyond the mere purpose of level progression. Furthermore, this sense of in-game presence connects the player to their avatar by way of shared experience, similar to how real-life relationships often deepen when people share a common problem or experience.

Virtual reality is, of course, aimed primarily at creating in-depth, immersive experiences, so more detached gameplay styles with third-person perspectives and well-defined protagonists are unlikely to be utilized much, if at all, in conjunction with the new technology. On the same token, they are just as unlikely to be impacted very much by the advent of VR gaming and, judging by the widespread, long-term popularity of more recognizable heroes like Link, Samus Aran, and Cloud Strife, they’re probably not disappearing any time soon, either.

As for first-person shooters, explorative puzzlers, first-person horror and action/adventure, these will be the primary hunting grounds of future VR-compatible video games. But what does this mean for the protagonists of those games? Hovering over a visible player-character like some sort of creepy, spectral presence third-person style is (mostly) out of the question; likewise, hearing someone else’s voice come out of your character’s mouth or running through your character’s brain, like Prince of Persia: The Two Thrones’s Dark Prince would be equally jarring.

This leaves VR gaming with two options: the silent/undeveloped protagonist (most likely of the Myst variety), or having at least a decent excuse for a player-character distinction – i.e. the character is insane and the player is their imaginary friend, or the character is manipulated or possessed by a god or demon, aka the player. All of those options, by the way, sound like really interesting game ideas.

The first option would require developers to either remove the character’s appearance entirely from the equation – by excluding reflective surfaces, for instance, or featuring an invisible protagonist – or to give players a fairly detailed level of character creation and customization. Luckily, the breakneck rate at which graphics have improved over the years suggests it probably won’t be too long before the latter route becomes a viable one. Protagonists would also have to be fully silent, meaning all dialogue choices would have to be eliminated entirely, or utilize either text-based responses or voice recognition technology, which would allow the player to respond in their own voice and take immersive gameplay to an entirely new depth.

Games featuring a player-character distinction, on the other hand, circumnavigate these problems with ease, and could even use them to narrative advantage. Putting a face and voice to the character the player is manipulating might create a sense of fellowship if the protagonist is sympathetically portrayed, or introduce a moral dilemma if the character suffers from the player’s possession. Alternatively, an irritating or outright evil protagonist could motivate the player to punish the character, try to change them for the better, or warp their personality further.

In any case, a VR game of this type would require far more aesthetic attention to detail than has been expected of third-person perspective games in the past. Being able to walk up to, circle, hover over, or climb inside the head of an in-game character is a far different animal from the current standard of watching from afar, or lurking just over the protagonist’s shoulder.

In the realm of virtual reality, true emotional depth would be difficult, although not impossible, to achieve if the character didn’t feel real. While great storytelling can convince us of the humanity of even the simplest of pixelated characters on a flat screen, through the lens of a VR headset, low-quality graphics or bad design would be infinitely more noticeable and more distracting, if not downright disturbing. Approaching a character that looks realistic from a distance only to realize their lip movements don’t match their speech and their eyes look like something out of an anime would be a little off-putting, to say the least.

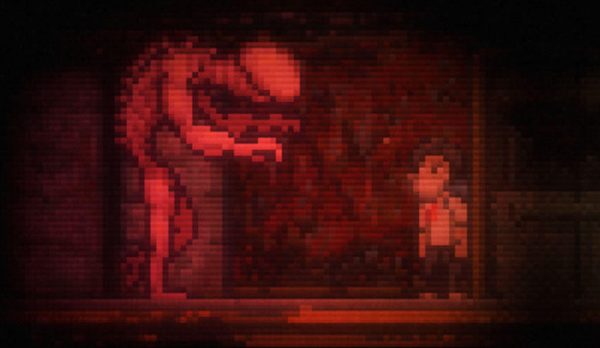

As with almost any issue in gaming, a few exceptions could make use of this aspect of VR gaming – for instance, a fantasy which puts players in a Pagemaster-esque situation by transporting them into an 8-bit world, or a horror game where everything is purposefully demented-looking – but for the most part, the more believable the experience, the better. There’s a reason they call it virtual reality.

Of course, the technology still has a few leaps and bounds to make before becoming a fully viable medium for these new narrative possibilities. Aside from the more general obstacles which, to some extent, all new consoles face (controlling costs in order to keep retail prices reasonable, ironing out glitches, etc.), virtual reality in particular will also have to overcome unique issues like concealing player-character height discrepancies, head tracking and motion-sensing glitches, and various safety hazards.

Sony’s recently-announced HMZ-T3Q and Oculus VR’s upcoming Oculus Rift both lay claim to head-tracking capabilities and cross-platform compatibility. The HMZ-T3Q may also include hazard detection, to warn players before they bump into real-world objects, while the Oculus Rift is compatible with other virtual reality tools like omnidirectional treadmills, with the latest prototype sporting a new motion tracking camera. Whether these headsets will live up to their potential or crash and burn, like Nintendo’s ill-fated Virtual Boy back in the ‘90s, remains to be seen, but if YouTube test runs are anything to go by, the Rift, at least, is showing serious promise, and Sony has never been one to lose ground for long.

Imagine a comfortable, lightweight headset, with beautifully-rendered panoramic 3-D graphics and fully functional head tracking paired with surround-sound headphones, an omni treadmill, and a precise motion tracking sensor – a suit like the PrioVR, perhaps, or wireless gloves like Mattel’s PowerGlove (but better), or even just a camera like the Kinect (but, again, better) – and working hazard detection. A vibration function could be added to any or all of these to simulate in-game collisions, and odor and wind simulators, like those Morton Heilig built for his Sensorama prototype in 1962, would also be a possibility. For fun, throw in superbly advanced versions of today’s voice recognition and artificial intelligence, which would allow for more complex dialogue options and more meaningful interactions between the player and a game’s NPCs.

If – and this is a big if – all this über-futuristic, multi-sensory technology could be properly formatted, coordinated, and perfected, the result would be, in a word, astounding. The line between player and character could diminish to the point of disappearing almost entirely. Of course, some barriers would be more difficult to cross – of all the senses, touch and taste would probably prove the most difficult to simulate – and some, including anything that would induce real physical pain or psychological damage, should never be crossed at all.

Yet, barring these, virtual reality has the potential to bring players and their avatars closer than ever before, opening the door to more complex, evocative, and more thoroughly interactive experiences than previously possible. At the brink of what could be yet another drastic change in technology, we’re standing together with our digital comrades and partners-in-crime, all of us keeping an eye on the virtual horizon and hoping for the best. The face of gaming is about to get a makeover, and so far, it’s looking good.

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!