For a medium so heavily dependent on visuals, it’s odd how easy it can be to overlook the sheer amount of detail work involved in video game creation. The more detail there is, the more likely it is the players will miss something: they can’t see the trees for the forest. With the possible exception of “art games” like Dear Esther and Journey (in which the entire point is art appreciation), developers have to all but program in neon signs screaming “Look over here!” if they want to draw the average player’s attention away from the main attraction – namely, the action – and get them to notice the little things.

Few “little” things seem quite so overlooked as works of art in gaming. Though a few hardcore forum threads and sites like Jon Gourley’s online Video Game Art Museum archive showcase and analyze such hidden gems, all too often the art remains exactly that: hidden. Rarely will an artist be given specific credit for designing this in-game portrait hanging on the wall or that statue looming over the level exit, and many players will speed right past them on the way to some virtual finish line (or while fleeing some terrifying enemy). Yet such background elements, trifling though they seem, require more effort to bring to life than some players need to complete entire games.

Why bother? What’s the point of spending precious time and energy on minor environmental features when there’s a whole world that needs building? The answer, to return to our earlier metaphor, is that without the trees, there wouldn’t be a forest. While including art in gaming isn’t the only way to add depth and detail to a digital otherworld, it’s certainly one of the most effective.

For instance: think back to all the countless jigsaw and sliding puzzles found in classic platformers and puzzlers. One of the most memorable 7th Guest brainteasers was the Stauf painting, an already unsettling portrait which, as the player progressed towards the solution, transformed a man into a devil, then a demon, then back into a man. Art may also function as a clue, rather than the riddle itself, or even quest items – think of the general’s strongbox in the Thief remake. And let’s not forget all the secret passages and bonus rooms hidden behind decorative busts and wall hangings, like the Hitler paintings found in Wolfenstein 3D.

But the purpose of art in gaming is not merely to prettify in-game surroundings or add a cultured, aesthetic quality to otherwise shallow challenges. A developer’s choice in décor carries serious atmospheric weight; a single design element can make or break the mood, to brilliant or disastrous effect. Horror games in particular draw on this power, utilizing the creep factor of threatening sculptures and eerie portraits of the dead and the damned, whose lifelike eyes follow players as they pass in darkened halls. Few can forget their first glimpse of the portrait of Alexander in Amnesia: The Dark Descent under the influence of dangerously low sanity levels, or the paintings in Nier which grew increasingly alarming with each subsequent glance. Likewise, anyone who played the second chapter of Saibot Studios’s Doorways will recall, with a sort of thrilled shudder, the mad Sculptor’s haunting creations.

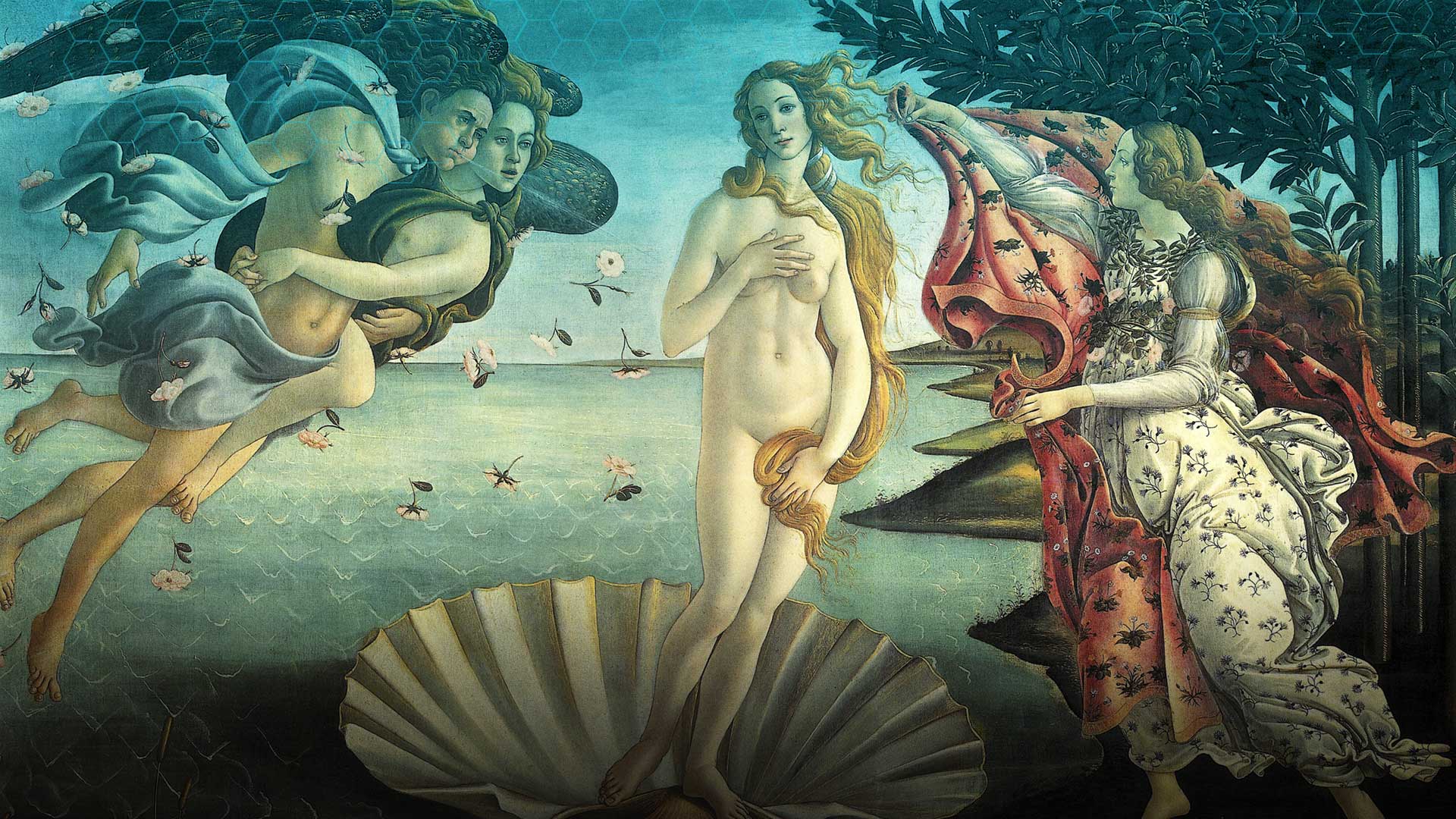

Of course, the effect is not limited to the horror genre. Gorgeous, vibrant stained glass images add fanciful color to the worlds of Kingdom Hearts and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and the bold, abstract pieces found in Mirror’s Edge are a perfect fit for the game’s unique and modern sense of style. In Mario 64, the paintings through which Mario traveled represented both the look and feel of the worlds they led to in just 8 bits. The Sims, in particular The Sims 3, frequently featured parodies of famous works and silly captions as part of the overall humorous attitude of the series. The Sokolov portraits in Dishonored, on the other hand, with their sepia tones and Victorian flair, emphasize the romantic, mysterious qualities (as well as the dark side) of the game’s fictional setting, the steampunk city of Dunwall.

The presence of art, in games as in life, can also serve as a cultural anchor. Games set in or inspired by real-world locations and time periods often include famous works of art to give players a sense of place. In the Tomb Raider series, ancient hieroglyphs help create the illusion that Laura is exploring real ruins, similar to how the paintings in Assassin’s Creed II play a big part in linking an improbable plot with actual historical events and locales. Even completely fictional worlds feel that much more expansive and immersive when given a past and mythology extending beyond a bare bones foundation and backed up by in-game artifacts the player can see, interact with, and learn from. The religious portraits strewn throughout Silent Hill 3, for example, allude to the beliefs of the town’s resident crazy cult, The Order, as well as the establishment (and, later, the transformation) of the town itself.

A similar goal is accomplished with the striking Founders statues of Bioshock: Infinite, with a twist: these sculptures, as almost all artwork in the series does, are also a commentary on both the in-game populace as well as real-world sociopolitical issues. By sheer size alone, these effigies tell the player something about the overbearing, overzealous nature of the group which erected them, thus not-so-subtly hinting that the same criticisms apply to a certain similar political party in the United States.

Though few games delve as deep and get as darkly political as the latest installment of Bioshock, it’s true that the art in games can also speak volumes in terms of characterization and plot. A mansion filled with exquisite marble figures and masterpieces framed in solid gold says the owner is (or was) wealthy, with an eye for art and expensive taste. If such pieces were, in fact, created by the owner or another in-game character, we get to go one step further and imagine their state of mind at the time of creation. In Clive Barker’s Undying, the perversely surreal portraits produced by the artist of the family, Aaron Covenant, allow players a brief, shocking glimpse into his macabre psyche – and sometimes, if the scrying stone is used, the past.

The protagonist’s interactions with, and reactions to, such may be equally revealing. Heather Mason makes it clear from the beginning of Silent Hill 3 that she is unimpressed by such creative feats, preferring less symbolic, more obvious modes of expression. Upon inspecting a painting titled “Repressor of Memories,” she remarks, “What the h*** kind of title is that? I don’t get this picture at all.” Later in the game, this is revealed as a particularly ironic hint regarding her personal history. Indeed, most, if not all, paintings found throughout the series have much to say about the main characters; one of the most memorable images from Silent Hill 2 is a rather telling portrait of Pyramid Head which may or may not have been either wholly fabricated or partially influenced by protagonist James Sunderland’s state of mind, while his reaction to the painting suggests just how oblivious to the truth he really is.

Games like kouri’s Ib take art-player interactivity one step further. Set in a haunted gallery, the game pits players against malevolent works of art bent on trapping the eponymous heroine forever. In this case, the art directly and aggressively affects the protagonist’s (and, by proxy, the player’s) state of mind, not to mention her well-being. The artworks also offer a more dynamic view than usual into the twisted soul of their maker, since, “It’s said that spirits dwell in objects into which people put their feelings.” Apparently, the artist had a bit of a homicidal streak.

Of course, all of this is still just the tip of the iceberg. The best games have all sorts of secrets to unlock, and not just the kind that grant amusingly-named achievements (“Chicken Kicker,” anyone?) or bonus items. Keen observers are rewarded with more memorable takeaways which linger long after the final level is complete. So next time you find yourself catching your breath between monster chases, or taking a brief break after finally chucking The World Eater himself back into the Abyss, don’t forget to stop and smell the roses – or at least do a little virtual sightseeing. It’s a shame to let hard work go to waste, and besides, you never know what you might discover. Or what might discover you.

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!

…WOOLY DESERVES BETTER LOL!